“Do you believe in fate?”

That’s what he asked me before telling me that he thought the reason we’d met was so that I could learn what I wanted in a partner, and vice versa. Intoxicated from the drink I’d had 3 hours earlier and annoyed, I replied, “maybe you’re right’ and fell into a deep sleep.

Reader, do you believe in fate? According to Merriam Webster, fate is “the will or principle or determining cause by which things in general are believed to come to be as they are or events to happen as they do”

When I think of fate, I think of what Christians refer to as “a calling.” A task placed in one’s hands or on one’s heart that is to be carried out by the chosen individual. Themes related to fate are everywhere and began to be pushed onto us from birth. It’s in children’s stories and in the names we’re given. From the moment of conception, parents start to imagine the kind of being they are creating and choose symbolic names for this being. God is in the details.

It feels fated that I ended up making clothes. I’ve had an interesting relationship with fashion and the space of beauty for as long as I can remember. I’ve always felt drawn to beautiful things and people, that means constantly walking a fine line between vanity and admiration for nature’s creations. Coming from a culture that places emphasis on STEM related fields and regards the latter as irrelevant or inessential, it can be a considerable feat. The struggle has been in shedding what I was taught to believe about the arts and embracing a new perspective. All my years of studying towards becoming a doctor have not been in vain.

It’s impossible for STEM fields to be as they are without imagination, dreams, and a prioritization of human life. According to Nika Dubrovsky and David Graeber, the art world exists in the same way that other institutions like patriarchy and capitalism do. They write in their 3-part articles (linked below), that the art world operates on a system of scarcity; meaning that access to, is limited as to create competition and further division in society. At the same time, “The art world, for all the importance of its museums, institutes, foundations, university departments, and the likes, is still organized primarily around the art market. The art market in turn is driven by finance capital. Being the world’s least regulated market…the art world might be said to represent a kind of experimental ground for the hammering-out of a certain ideal of freedom appropriate to the current rule of finance capital” (part 1 article). Furthermore, they state that the art world is controlled in terms of production, meaning that what is constructed must fit within the confines of what the elite deem appropriate. In part 2, they detail how the art world leans on the invisibility of struggle to mask the real implications of what it means to be an artist and in turn this act of shielding the production details shapes consumer. They relate this to the factory system. Nika Dubrovsky and David Graeber, state that “Consumers were confronted with two different sorts of commodity: on the one hand, an endless outpouring of consumer goods, produced by a faceless mass of industrial workers, about whose individual biographies consumers knew absolutely nothing (often, not even what countries they lived, languages they spoke, whether they were men, women, or children…)…” In essence, the consumer/buyer is shielded from the reality of manufacturing by both the mass production and consumption of goods by the world around them. It’s purposefully done that goods appear almost silently and are born out of the dark. And this matters because its political work.

The fashion/beauty industry operates within the world of art. Now think the likes of Elsa Schiaparelli, who’s work involved engaging with the elites and eventually led to a shutdown of her store in Paris. Fashion can be and is political, furthermore, it must be regarded seriously as such. According to Andrew Bolton in Vogue’s Power Dressing: Charting the Influence of Politics on Fashion, “Fashion functions as a mirror to our times, so it is inherently political. It’s been used to express patriotic, nationalistic, and propagandistic tendencies as well as complex issues related to class, race, ethnicity, gender, and sexuality.” Additionally keep in mind that it is “a planet-spanning $2.5 trillion business…[that] is responsible for as much as 10 percent of annual global carbon emissions.” In the same article, Marine Serre, is quoted saying “Every choice you make as a company will influence the world." What you make, how you make it, how you speak about what you’ve made- for me, everything is politics.” And Virgil Abloh said, “…There’s the politics on your phone and the politics on your street. And yeah, there’s the politics of your clothes.” And so, reader, fashion is political. The mechanisms in which the things you wear are created and the ways in which they reach you, all of this has implications that go beyond your scope. They matter. The arts matter.

My fashion friend speaks on how conglomerates like LVMH prioritize innovation and sustainability through a system of recruitment of artists and designers that can carry out already established methods production. She further states that based on her observations, much of production and expansion of the company is based around repackaging previously manufactured products and releasing them under a “new” lens/perspective. Essentially, a recycling of sorts. This is important because it highlights the art world (including beauty/fashion) as needing a serious shift in its functionality. Reader, do repackaged goods sound like the epitome of innovation? The same outfit, produced by the same manufacturers, just under 30 different brands is innovation? (LVMH, please hire me in your sustainability department so I can help you regroup and rethink your sustainability efforts for the environment. Take my critique as a sign of boldness and strength… I await your email :). )

To regroup, I have been shedding previous notions I had of the art world. Calling myself an artist (or designer) now has become more than just about my ability and passion for creating. It’s been also about taking responsibility for how my creations impact my audience. Every tool I use, including the body of mine, has a story. My job is to listen to its story, figure out its origins and then contemplate how it fits into the society of today. And most importantly, how I want it to fit into society or even if I want it to fit.

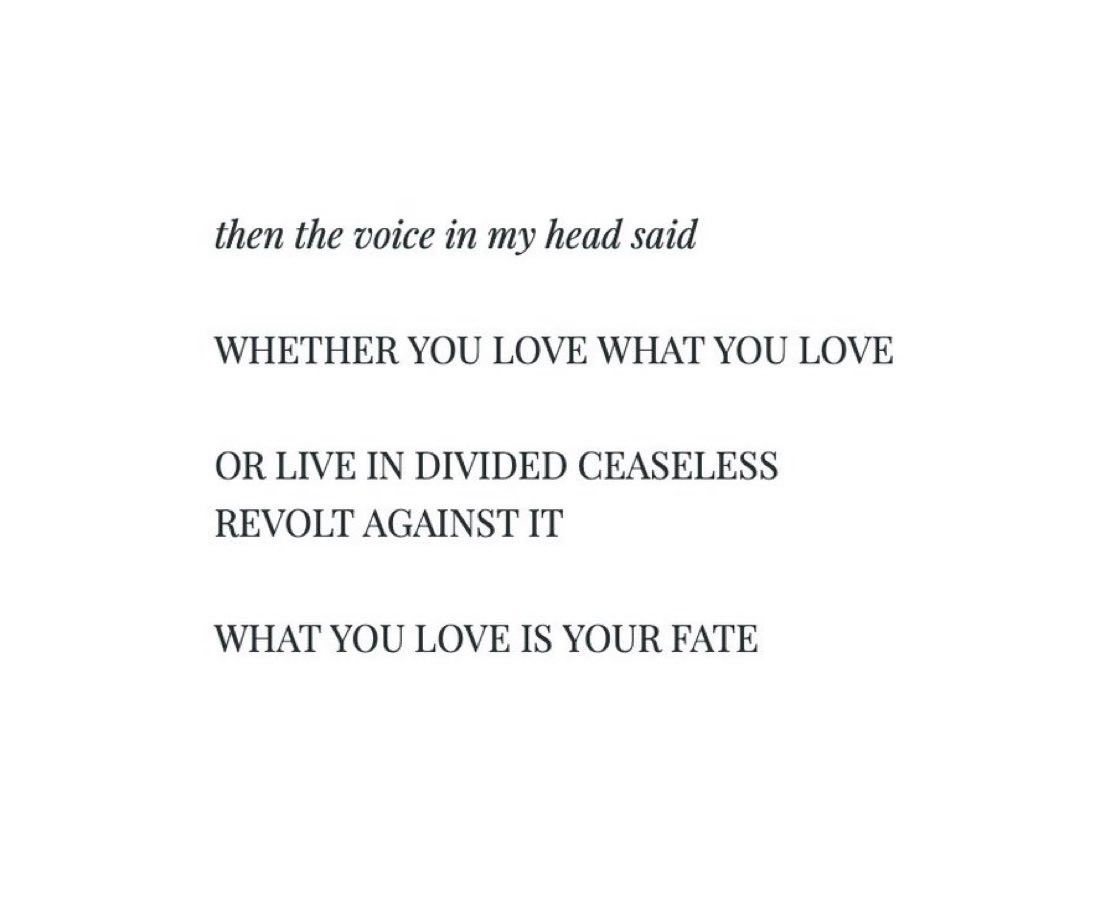

Fate. I believe in fate. And the fate of the world lies in everyone’s hands. The fate of the art world, of fashion, and of beauty depends on how seriously we began to prioritize the tangible impacts of human psychology. The mind is the most powerful source of creation. Everything around you- from the chair you sit on, the home you sit in, and the clothes you wear all began as a thought. Fashion is not only a tool, but a language that is utilized to shape society. Do you know who makes your clothes? Do you know the origins of tools utilized to produce the phone you hold? The sunglasses you wear- what inspired the designer to make them and why? All of this matters. Art informs every aspect of your existence. There is no STEM without the world art. Art came first. The world of art requires giving up a lazy and passive way of being and calls to take on an active role in creating a world habitable for everyone.

That is the fate of the artist.

Articles mentioned:

Another Art World, Part 3: Policing and Symbolic Order - Journal #113 (e-flux.com) (part 1 and 2 are linked in 3 here)

xoxo,

Kayitesi.